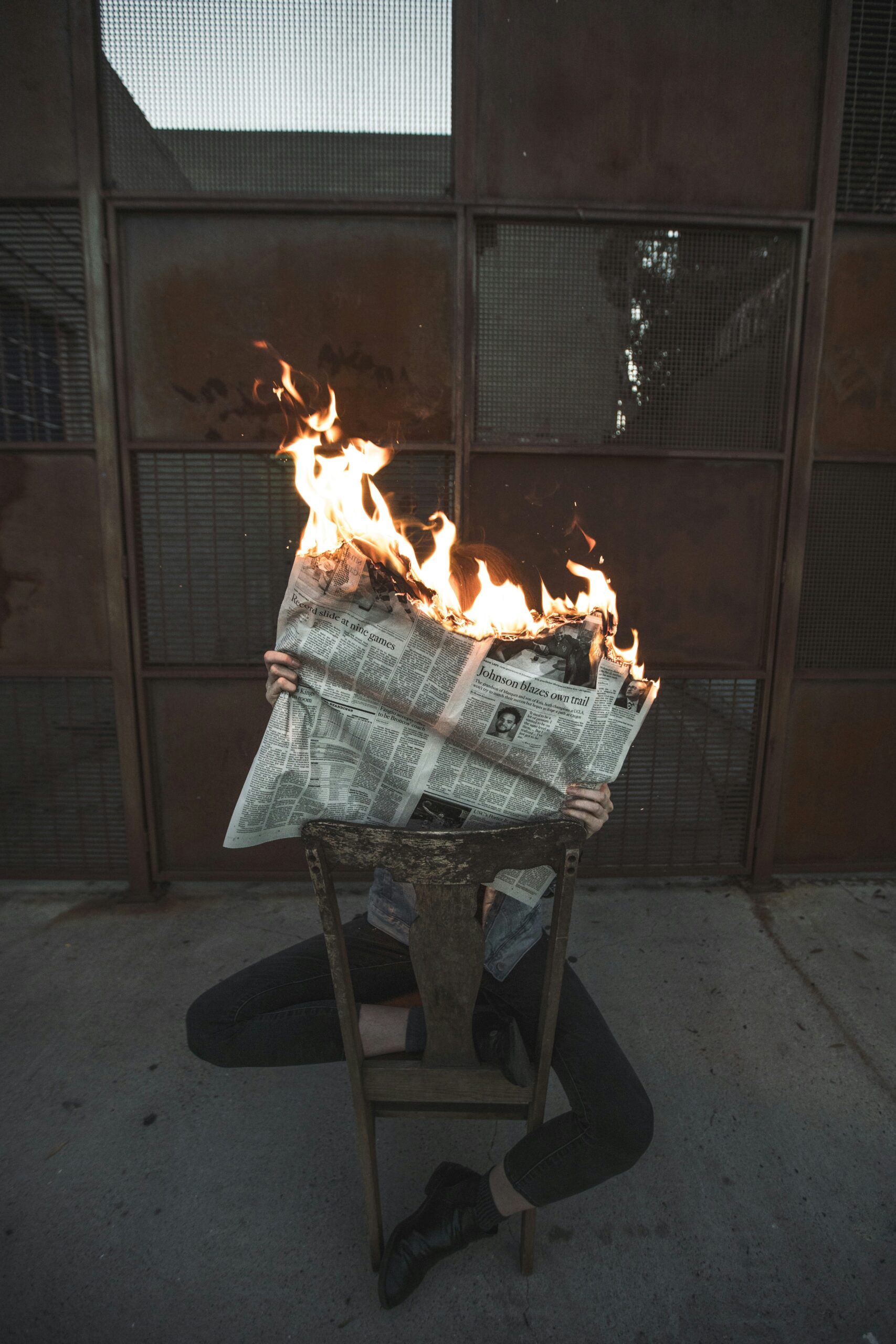

Journalism students see an industry in crisis. It’s time to talk about it

It’s hard not to see the journalism industry as one in crisis.

In February, Bell Media announced it was ending multiple CTV newscasts, making other programming cuts and selling 45 radio stations. Its parent company, BCE Inc., also announced it is cutting 4,800 jobs “at all levels of the company,” saying fewer than 10 per cent are at Bell Media.

Weeks later, Vice Media said it would stop publishing on Vice.com and lay off hundreds.

These decisions followed CBC’s December 2023 announcement that it would cut 600 positions, and news last fall that some Canadian journalism schools had shut down or paused their programs.

Across the country, the outlook for the future of news is — at best — uncertain. Not talking about the state of the industry is not an option for journalism educators.

In journalism school, students learn their craft while engaging with critical questions about their roles and responsibilities. They are often taught by previous or current journalists, whose work experiences prepare them to help students tackle reporting challenges.

Crises ask journalism educators, students and practitioners to grapple with sharing stories about what the future could hold. What will journalists’ jobs look like in five years? Or 25 years?

No one in any industry would be able to answer such questions with certainty. But critical events in journalism demand we talk through uncertain futures. And this presents follow-up questions. What are the risks and rewards of talking openly about precarity? How do you start a conversation when the future is so uncertain?

Understanding journalism education

In 2015, with the shock of the 2008 economic crisis still working through newsrooms, journalism educators offered a wide-ranging map for reevaluating the goals of journalism schools, and whether they are solely meant to train future journalists.

Crises run into each other, overlapping and informing responses to change. COVID-19 and a reckoning with racism in journalism and other institutions have demanded new reflections on journalism education.

Pathways to the future

It’s time journalism educators shift conversations with students, to address their experiences, their worries and their understanding of what journalism is and what they want it to be.

In 2022, we asked journalism students at Carleton University — where we, respectively, teach and studied — how they felt about their training through COVID-19. We were curious about how students viewed online learning and transitioning into journalism jobs.

What we heard were concerns about burnout, precarity, work-life balance and the long-term outlook for a life in journalism.

“I just feel like almost every week or every few weeks, I go on Twitter and there’s a journalist who’s like in their 30s or 40s, like halfway through their career, who just quit,” one student said.

Students knew the risks of going into the industry, thanks to news of other cutbacks, guest speaker testimonies and their own experiences losing internship opportunities when the pandemic forced newsrooms online.

Anticipating challenges

We asked journalism students what they thought a day in the life of a journalist looked like. They talked about days that demanded endurance, dedication and working through different kinds of uncertainty.

“They’re just always on,” one student said. “I don’t think journalists have a normal day. As in, you know, get up, get to work, get home.”

Another student described “general burnout” as “a huge part” of the job.

It isn’t surprising that students anticipated challenges finding work and worried about long-term financial stability. In some ways, their responses align with a broader Gen-Z refusal to put their jobs at the centre of their lives or accept low pay.

“I don’t want to say, you know, the more money you make the more successful you are, but being able to just have that security is, I think, a huge thing,” one student said.

“Maybe it doesn’t quite align with ‘success’ in a ‘making a difference’ kind of way. But I think (financial security) gives you an ability to make a difference.”

Students also flagged the importance of mental health and well-being.

“There is an expectation that your entire life should revolve around chasing a story until you physically cannot anymore,” one student said, explaining that this kind of thinking turned them away from journalism.

Learning together

Today’s journalism students have likely been told their entire lives — by friends, family, pop culture and so many reports — that it’s a dying industry. Nonetheless, they’re driven to find out more.

Journalism in crisis, as others have argued, presents an opportunity to unpack traditions and reimagine practices.

It’s also an opportunity to reconsider how journalism schools and newsrooms respond to the concerns of emerging journalists. How can precarity and burnout be addressed collectively inside and outside journalism, not as individual matters?

One place this can begin is with classroom conversations, collectively taking on uncomfortable truths and fears alongside building new skills.

Navigating not having reassuring answers

One risk, for educators, is not having ready-made, reassuring answers to questions of insecurity.

Introducing worst-case scenarios also risks scaring away students. In our interviews, one student cautioned against presenting guest speakers’ negative portrayals of the industry too early, for example.

But recent news makes industry crises impossible not to talk about.

Talking through crises can allow for discussion of alternatives and solutions. However, care should be taken to not romanticize what has worked in the past, including precarious conditions like long hours, low pay or competing for fewer and fewer jobs.

Instead, it’s helpful to think of imagining different journalism futures as an in-progress collaboration for students, educators, journalists and news organization leaders. Such collaboration is a project of articulating not only crisis conditions, but drawing on shared experiences to figure out what it would take to make things better.

Looking back, we wonder what responses and creative solutions we would have heard if we asked students what they wanted their days to look like as journalists — not just what they thought the job looked like already.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Trish Audette-Longo is an assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University in Ottawa.

Christianna Alexiou is a writer, editor and researcher experienced in journalism and strategic communications in both corporate and public-sector spaces. She is a current MSc in Regulation student at the London School of Economics and received her Bachelor in Journalism Honours with a double minor in Law and Spanish from Carleton University in 2022.